"SOS from Arizona's Other Death Row"

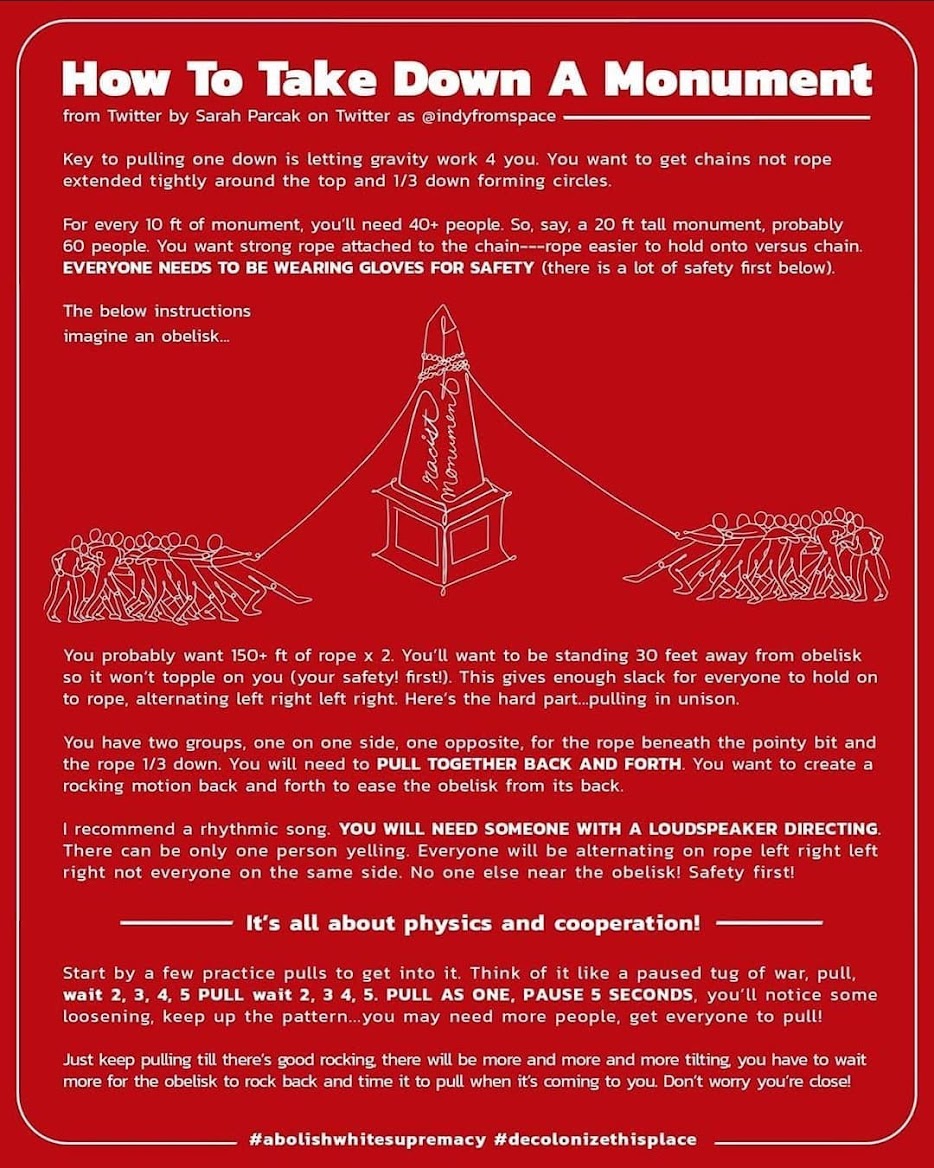

40-foot community mural in chalk, from rooftop

Firehouse Gallery, Phoenix (July 2012)

This

blog post goes out to those of you trying to help a prisoner in

Arizona’s Department of Corrections get into protective custody, or

otherwise “safe” housing. I put that in quotation marks because prisons

are inherently unsafe as heteropatriarchal state institutions of

control, designed to brutalize people without leaving marks on their

skin, and need to be eradicated, not merely reformed. The movement to do

so will not succeed without the participation of today’s prisoners,

though, which means they need to be able to survive their incarceration

relatively intact in order to lend their voice and critique to the

collective struggle for liberation.

Towards

that end, I recently updated the letter I send to all the state

prisoners who write asking for help seeking protective custody, which I

will soon also post as a blog. At the bottom of this note is a set of

links to that letter and the other documents I send out when a prisoner

tells me that he or she is in danger (the letter is written to both the

men and the transgender women in men's prisons because that's where all

the 805 requests come to me from, not because those at the women’s

prison don’t experience violence).

If

you are able to do so, please print and send these materials to your

loved ones yourselves, allowing me to use my resources for prisoners who

have no one else to help them. It'll probably cost about $5 to print

and send everything first class. Then send me an email letting me know

you used these resources, and why, so I can keep track of the issues

arising in the prisons and get back to you if needed. Your feedback on

what's useful and what's confusing - and corrections where I've been

mistaken or something has changed - are really helpful, too. Find me at arizonaprisonwatch@gmail.com.

If

your imprisoned friend or loved one is LGBTQ, whatever their current

situation in prison, ask them to please write to me (sorry, all - I'm taking care of my own family now..you need to take care of eachother, now). We’re building a small network of

support in the community in hopes of engaging attorneys and other queer

activists in the struggle of our people behind bars in this state;

unless they ask me not to, I will share their stories with these allies.

Their voices are needed to help others out here understand their

experience and how best to intervene in the prison industrial complex.

Tell them that I identify as queer myself, and am in correspondence with

about 30 LGBTQ prisoners in AZ right now, many over issues related to

being safely housed. If there’s anything I can do to help them, I will.

Also,

if you have a loved one currently going through the 805 process, make

sure to provide them with as much emotional support, validation, and

mental stimulation as possible. While they're in the hole wondering if

they're going to live to see you all again, be sure to send plenty of

letters, get the kids to draw pictures, send them articles they might be

interested in, reminding them of the best parts of who they are.

Encourage them to read, write, draw, or to somehow keep their mind

creatively engaged as much as possible.

If

you grow concerned about their risk for suicide for some reason, be

very careful about telling the DOC that they may be in danger of harming

themselves - there will be consequences that may keep them from

trusting you with their feelings again, and this ordeal will likely not

end soon. The cell they get placed in “for their safety” will probably

be cold and completely bare, they may be stripped to their shorts - or

even to nothing - by guards who mock them if they cry, the walls or

floor may still be smeared in blood or feces from the last guy, and they

lose all ability to communicate with the rest of us until their mental

health "improves". They may even be shot up involuntarily with

mind-altering drugs, or strapped down in 4-point restraints (during

which time some have also been abused by the staff attending them).

See,

suicide watch at the DOC is designed expressly to cover the state's ass

in the heat of the moment by physically preventing someone from

self-destruction, while the experience for the prisoner can be even more

traumatizing than that which they are trying to escape. To alleviate

this whole new level of suffering, prisoners are then compelled to

assure the doctor he won't be liable if they do kill themselves - and

some then simply make damn sure they don't fail in their next attempt,

so they never have to endure being “saved” like that again. In fact, the

protocol for suicide watch at the AZ DOC is a large piece of the class

action lawsuit against the AZ DOC regarding health care for prisoners

(Parsons v Ryan). If you think you absolutely have to tell someone at

the prison to intervene to protect them from themselves, then do so. I

can’t make that call from here, and you are the one who will have to

live with it, however things turn out.

Now, I'm no mental health expert, so bear that in mind. I've just spent a lot of time learning to be present with people in their grief and fear. Whenever I'm concerned about the risk of prisoner suicide, I

try to summon the survivor they have deep within, and call on them to

become the superheroes of their own lives - no one else can be. They

really do need superhuman strength to face the fear of what may still

lie ahead for them in prison, and whatever you can do to help them

visualize that, to convince them they can endure this period in their

lives and perhaps even turn it to good use for others, will help them

far more than the prison shrink and the subtherapeutic dose of drugs he

might offer.

Know

that what the captive human being experiences at times is terror and

the desire to flee beyond anything the free person can conceive, and

they have to navigate very complex dynamics from a place where they have

been systematically stripped of their identity while being demonized,

dehumanized, devalued, and literally enslaved. Make sure they know that

the people who love them need them to survive this crisis, and if for

some reason they can't trust you with their fear, help them connect with

someone they can trust. Maybe there's an old friend who could write to

them and ask if they're okay, while reaffirming that they have not

already ceased to exist to the rest of the world.

Do

whatever you can think of to keep them connected to you and others they

love, and make them promise you they won't bail out, because those

detention cells take a lot of lives. Make them promise often, and tell

them you need to trust them to live up to it, to not abandon you. You

must help them fight despair and hopelessness with as much vigor as you

put into the fight with the state. More prisoners die from suicide than

homicide every year, and many do so out of isolation and fear, right

where your loved one is now.

Reassure

them that they can still maintain meaningful relationships with people

out here - many do with me, and have for several years - while

developing more compassion and maturity as human beings. They can choose

to spend their time making amends to humanity for whatever harm they

may have done (if any, keeping in mind that not all crimes have victims,

and not all of the convicted are guilty) by helping those around them

whenever they get a chance - the prisons are full of the disabled, sick,

and dying. The DOC won't facilitate that kind of personal growth,

though - they are their primary abusers behind bars, instead. Anything

your loved one does to become a better human being will be all to their

own credit, not the DOC's.

The

prison administration will try to intimidate both prisoners and their

families into silence by reinforcing your social isolation with shame,

and your feelings of vulnerability with their authoritative denials of

the danger your loved ones are in. They will trivialize your concerns,

chastise you, blame you or the prisoner for their endangerment or your

extortion, and appease and/or condescend to you in an effort to get you

to surrender to their assertions that their judgement is unassailable,

as are their intentions to protect all prisoners from harm, and back

off.

While

lying to the legislature and the public about conditions in the prisons

today and assuring us all that he's doing a swell job, the AZ DOC

director’s most static message to prisoners under this administration

has been that they have no right to expect to be safe or get medical

attention when needed, or to protest the conditions of their confinement

- some are retaliated against ruthlessly when they do.

The

implication is that once convicted by a system that pretends to be

just, Arizona’s prisoners are considered to be worthless, disposable

human beings, whatever the reason they are in prison. That’s reinforced

from the governor of this state on down. Do not succumb to the

relentless messaging you may get from media or politicians that they are

right and the criminal is never to be trusted. If a prisoner tells you

they are in danger or have been hurt, give them the benefit of the

doubt, and recognize that the state itself is the main perpetrator of

violence against them, not a well-meaning co-parent some mothers like to

think it is - do not even communicate with people at the prison without

understanding that fundamental dynamic first.

Some

individual staff may be more compassionate and pleasant to speak to

than others - and alliances where your loved one is housed or receives

health care are important to build. Just remember that the AZ DOC cares

only for its own survival, not for the comfort, safety or welfare of its

prisoners. No matter how much you appeal to the notions of mercy or

justice as you fight (not plead) for the life of your loved one, you

must show

(not simply threaten) the state you can hurt it badly if your loved one

isn’t properly cared for. Ultimately this may mean both engaging reluctant legislators in your fight, and helping prisoners go ahead and file their

own Section 1983 civil rights suit. Otherwise, the DOC will continue to

prioritize the needs of the few criminals who still have money and

power, and ignore you until you give up and go away. You’d be surprised

at how many people do just that. Don’t be one of them.

The

more concrete instructions for how to navigate the 805 process are

embedded below. Feel free to call me (Peggy Plews) with questions, too,

at 480-580-6807, or email me at arizonaprisonwatch@gmail.com. If the prisoner is already denied thier appeal and wants to file their Section 1983 suits, there are resources in the side column of the Jailhouse Lawyers' Auxiliary Guild - AZ blog to help them.

does not substitute for following policy)

(fight those RTH tickets)

additional resources, depending on special needs:

The National Lawyers Guild Complete Jailhouse Lawyers Handbook

(big PDF to print but worth it. helpful for filing section 1983 claims)

* Even if they can’t help in your individual case, the ACLU needs to know what’s happening as far as the violence in the prisons and the classification issues go. When sending in complaints, prisoners should also ask the ACLU for a copy of the Parsons v Ryan case about their health care.

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)